Tuesday, March 05, 2024

A Browne bookshelf

Sunday, August 27, 2023

'Compassion is the physician's teacher' : Gavin Francis - 'The Opium of Time'

Dr. Francis joins the ranks of other physicians who have admired Thomas Browne, these include the distinguished Canadian doctor William Osler (1849-1919), the surgeon Sir Geoffrey Keynes, and the Norwich-based GP Anthony Batty-Shaw (1922-2015). Much of the strength of Dr. Francis's appreciation rests in a shared profession for although separated by centuries he recognises that, in many ways little has changed in the role of his profession since Browne's day. Faced with human illness and suffering the role of the physician as a well-informed and trusted confidant has altered little. In this respect The Opium of Time transcends the technicalities of literary criticism, highlighting Browne's tolerance, humility and compassion as key components of a shared humanism. The discourse Urn-Burial and Christian Morals in particular are favoured by the author as exemplary of Browne's psychological understanding of the human condition, encapsulated in pithy aphorisms such as 'Sorrows destroy us or themselves'.

Its refreshing to read in The Opium of Time of the influence of the Swiss alchemist-physician Paracelsus (1493-1541). During his short life Paracelsus dedicated himself to the art of healing, declaring 'Compassion is the physician's teacher'. Crucially, he urged physicians to experiment upon nature's properties in order to discover new chemicals for medical use, Browne himself knew 'that every plant might receive a name according unto the disease it cureth, was the wish of Paracelsus' [1] As a critical follower of Paracelsus, Browne, like the Swiss physician, was both early chemist and alchemist, the difference between the two activities being fluid not fixed, even with latter scientific figures such as Robert Boyle (1627-91) and Isaac Newton (1643-1727).

Its primarily because of Dr. Francis's non-judgemental mention of the influence of Paracelsian medicine when others have either denounced, or what's worse, ridiculed Browne's 'spagyric' medicine (the Paracelsian neologism 'spagyric' is inscribed in verse on Browne's coffin-plate) that The Opium of Time can be said to be the most insightful book by a medical professional on Browne since William Osler's day, over a century ago.

The parallel between the humility of Christian faith and the humility of caring work in nursing and medicine is noted by Dr. Francis, a staunch advocate of the beloved but beleaguered institute founded upon Christian values known as the NHS. In Browne's day devout physicians took inspiration from Christ's Ministry. [2] While not sharing his subject's religious faith, Dr. Francis nevertheless applauds Browne's Christian stoicism, engendered one suspects, by a shared close proximity to human suffering and mortality in profession.

Gavin Francis also highlights Browne's little-recognised sense of humour, a tool which used carefully, he suggests, can assist the doctor-patient relationship when faced with seemingly unsurpassable dilemmas. Humour is encountered throughout Browne's writings. His quip on William Harvey's detection of the circulation of the blood as being, “a discovery I prefer to that of Columbus” (i.e that of America) [3] is typical of his dry and learned humour. Browne's most sustained piece of humour is the hilarious, 'To an illustrious friend on his wearisome Chatterer' . It may have been composed in order to cheer up his friend Joseph Hall (1574-1656) who was deposed as Bishop Of Norwich in 1643 for supporting the Royalist cause.

In addition to examining the influence of piety and humility upon Browne's intellect and spirituality, Dr. Francis also tackles the thorny subject of the physician's involvement in a witch trial, discussing how much he was influenced by the endemic misogyny of his era. Browne never testified at the Bury trial, nor could his opinion have influenced any verdict while the patriarchal authority of the Judaic Old Testament held blind sway over reason. A single verse in the Old Testament sanctioned and 'justified' the legal condemnation to death of what is estimated to have been a quarter million of mostly women throughout Europe from 1400-1700. [4]

Much has been made on what is one of the very few biographical details known about Browne, often inviting disapproval from a comfortably removed historical perspective. His culpability and supposed failure in risking his status and social standing when faced with mass-mind irrationality and legalized prejudice is often exaggerated. Its worthwhile remembering, as Dr. Francis does, that Browne dedicated a large part of his life to relieving the suffering of others. His psychological observation that, 'No man can justly censure or condemn another because indeed no man truly knows another' seems applicable here. [5]

Dr. Francis shares with his subject in a love of travel, both doctors recognising that travel usually broadens the mind in tolerance, understanding and appreciation of different societies and cultures. Its thus an easy excuse for the author to visit Padua in Italy and Leiden in the Netherlands in search of traces of Browne's academic sojourns.

Replete with original observations which others have overlooked, Dr. Francis also draws attention to how Thomas Browne when elderly, enjoyed reading, or having read to him, accounts by traveller's from distant lands such as Africa, India and China. Throughout The Opium of Time one also learns more of Dr. Francis's own extensive travels which have included working visits to India and Africa as well as Antarctica.

In a book engaging in narrative, the author takes delight as many others, in Browne's inventive coining of new words into the English language. Browne's neologisms catered for the need for a preciser vocabulary in the early scientific revolution and many, such as 'electricity' 'ambidextrous' 'network' cater for this need. Through his deep study and understanding of Greek and Latin Browne is also credited with introducing words associated with his profession such as 'medical', 'pathology' and 'hallucination' for example.

Thomas Browne gave good advice to literary critics when declaring - 'If the substantial subject be well forged we need not examine the sparks which fly irregularly from it'. [6]

The Opium of Time is a wholly original response to the Renaissance humanism, wit and scholarship of Thomas Browne, nevertheless a few 'irregular sparks' fly from it, silently smouldering in the deep pile carpet of truth. Credence is given to the unreliable narrator of W.G. Sebald's The Rings of Saturn who mischievously supplements fictitious text to the conclusion of The Garden of Cyrus. A footnote regret that Aldrovandi's Monstrorum Historia would not have been known to Browne is groundless. Throughout his life Browne kept well-abreast on the latest publications, nationally and internationally. The Sales Auction Catalogue of his and his eldest son Edward's combined libraries is solid evidence of the vast and extraordinary range of Browne's interests. The 1711 catalogue records that Aldrovandi's Monstrorum Historia (picture below) along with some half a dozen other titles by the Italian zoologist are listed as once in his library. [7]

Nor can one agree that Browne's choice of a 'provincial general practise' is exemplary of his humility. Norwich was England's second city in Browne's day, a position it occupied until the early Industrial Revolution. Densely populated and surrounded by a highly-productive agricultural hinterland, the ancient City had important links in trade, culture and travel to mainland Europe, in particular the Netherlands. As the home to a wealthy gentry who were financially able to consult and afford a doctor's fees, Norwich was an ideal location for an ambitious, newly-qualified physician to establish a medical practise in order to support a wife, home and family.

But a greater weakness of The Opium of Time is its author's reluctance to acknowledge Browne's esoteric inclinations, resulting in an incomplete portrait of the seventeenth century physician-philosopher. Other than a welcome mention of the medical influence of Paracelsus, Dr. Francis is reluctant to discuss Browne's relationship to esotericism. Its a reluctance which results in the removal of a sentence of text. An entire sentence in which Browne makes a tacit nod to like-minded influences upon him, 'It was the opinion of Plate and is yet of the Hermetical philosophers', is removed and replaced thus .... and not presumably for the purposes of page formatting or in order to save ink. [8]

Such glossing over of Browne's esoteric credentials is regrettable. Its a slippery path to travel upon if, for example, one dislikes the sentiment expressed in a few bars of a Beethoven symphony or imagery in the lines of a Shakespeare sonnet to simply extract and omit them from a work of art.

It's usually the British historian Dame Frances Yates (1899-1981) who is credited as the first to explore the vital influence which Western esotericism wielded upon scientists, thinkers and artists of the Renaissance-era. Yates demonstrated Western esotericism to be worthy of academic study. Catholic in faith herself, she also disproved a commonplace misapprehension, that its necessary to personally believe ideas espoused by Western esotericism when studying its influence in intellectual history.

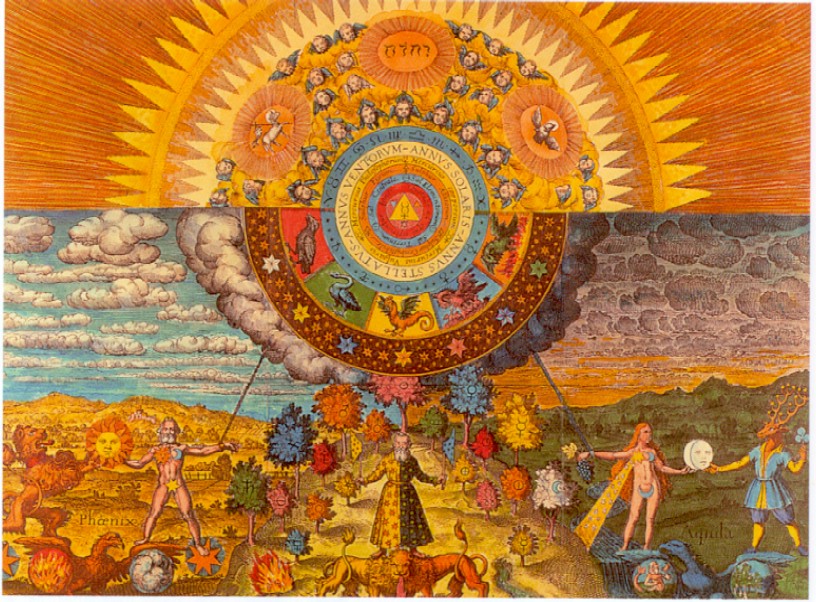

Ever since the humanist scholar Marsilio Ficino (1433-99) introduced Plato's Timaeus to Western readers and attributed his translation of the Corpus Hermeticum to the mythic Hermes Trismegistus, numerous thinkers, scholars and artists throughout the Renaissance era (circa 1500-1650) studied and were influenced by Western esoteric concepts such as Neoplatonism, Hermetic philosophy, Cabala, Gnosticism and alchemical symbolism which they incorporated into their art, philosophy or science. Thomas Browne, in common with British contemporaries such as the Welsh clergyman Thomas Vaughan (1621-1666) the Oxford antiquarian Elias Ashmole (1617-92), the Paracelsian physician Robert Fludd (1574-1637) and Arthur Dee (1579-1651) eldest son of the Elizabethan magus John Dee were influenced by the tenets of Western esotericism. Thomas Browne makes clear his allegiance in Religio Medici when emphatically declaring, 'the severe schools shall never laugh me out of the philosophy of Hermes wherein as in a portrait things are not truly seen but in equivocal shapes'. [9] There's no evidence he ever deviated from this opinion in his life-time. Even in Christian Morals a moralistic work believed to have been written late in his life during the mid 1670's which Dr. Francis refreshingly champions for its many profound psychological observations, mention of astrology, physiognomy, the alchemical maxim solve et coagula along with the mythic Hermes Trismegistus can be found.

The Garden of Cyrus has been described as 'the ultimate test of one's response to Browne'. For Dr. Francis and for many others, its 'the strangest of all Browne's books'. Consulting the well-worn role-call of Browne's literary critics little assists comprehension of its hermetic content. Dr. Johnson from the height of his 18th century Age of Reason in particular was unsympathetic and disparaging towards it. Modern scholarship however recognises a helpful interpreter, one who Gavin Francis mentions in his 'Shapeshifters: A Doctor's Notes on Medicine and Human change' namely the Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961). Through a judicious application of C.G. Jung's life-long study and understanding of Western esotericism its possible to acquire new insights on Browne's inventive creativity and literary symbolism.

Dr. Francis notes of a passage in Urn-Burial, that - 'It is almost as if Browne wished death and new life to sit adjacent on the page. He seemed to want to demonstrate the fraternity of life and death, their interdependence.' But in fact its more through the physical binding and union of the diptych discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus that Browne ingeniously demonstrates this fraternity. The somber, saturnine speculations of Urn-Burial are 'answered" by the mercurial garden delights of Cyrus. The gordian knot as to why they exhibit a plethora of oppositions or polarities in respective themes, truths and imagery such as - Decay and Growth, Mortality and Eternity, Body and Soul, Accident and Design, Speculation and Revelation, Darkness and Light, World and Universe, Microcosm and Macrocosm, is sundered in C. G. Jung's sharp observation - 'the alchemystical philosophers made the opposites and their union their chiefest concern'. [10]

Jung's lifetime study of comparative religion and alchemical literature also assists in identifying the source of imagery at the apotheosis of Browne's Urn-Burial in which he states, 'Life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible sun within us'. Browne's 'astral imagery' in this case originates from his reading and 'borrowing' imagery by the Belgian alchemist and foremost advocate of Paracelsus, Gerard Dorn whose writings feature in the alchemical anthology known as the Theatrum Chemicum. [11]

All of which strongly suggests Browne's esoteric inclinations are far greater than usually is acknowledged and none of which distracts from enjoyment of what is a personal appreciation.

Slender in volume but compressed with original observations and well-attuned in empathy with its subject, The Opium of Time will hopefully be enjoyed and enlighten its readers, long may it remain in print. Opium however, in Browne's proper-name symbolism is invariably associated with Oblivion, the philosopher of the Oblivion of Time in Urn-Burial knowing that ultimately little survives the devouring of Time.

Books consulted

* The Opium of Time: Gavin Francis OUP 2023

* Shapeshifters: A doctor's notes on medicine and human change Gavin Francis Wellcome Collection 2016

* The Major Works of Sir Thomas Browne edited and with an Introduction by C. A. Patrides Penguin 1977

* A Catalogue of the Libraries of Sir Thomas Browne and Dr Edward Browne, his son. A Facsimile Reproduction with an Introduction, Notes and Index by J.S. Finch pub. E. J .Brill 1986

See also

* The Opium of Time Opiate imagery and drugs in Thomas Browne's literary works. (2016)

* Carl Jung and Thomas Browne On the extraordinary relationship between Jung and Browne

* Paracelsus and Sir Thomas Browne

* A selection of books in Thomas Browne's library

* To an illustrious friend on his wearisome Chatterer

Notes

[1] Pseudodoxia Epidemica Book 2 chapter 7

[2] 'And Jesus went about all Galilee ....healing all manner of sickness and all manner of disease among the people.' Matthew 4:23

[3] In Browne's correspondence to Henry Power

[4] 'Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live' (Exodus 22 verse 18)

[5] Religio Medici Part 2:4

[6] Christian Morals Part 2: Section 2

[7] Aldrovandi's Monstrorum Historicum Bologna 1642. 1711 Sales Catalogue page 18 no. 23

[8] Religio Medici Part 1: 32

[9] Religio Medici Part 1 : 12

[10] In foreword to C.G. Jung's Mysterium Coniunctionis (C.W. vol. 14)

[11] Over 900 pages of Dorn's writings feature in the first volume of the foremost alchemical anthology of the 17th century, the Theatrum Chemicum. Browne's copy listed Sales Catalogue. page 25 no. 124.

Jung even took a copy of the Theatrum Chemicum with him when visiting India. In his Mysterium Coniunctionis he states - 'In Dorn's view there is in man an 'invisible sun', which he identifies with the Archeus. This sun is identical with the 'sun in the earth'. The invisible sun enkindles an elemental fire which consumes man's substance and reduces his body to the prima materia'. - CW. 14: 49

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

'In the bed of Cleopatra' - Thomas Browne's Egyptology

Thomas Browne's study of ancient Egypt was multi-faceted; as a doctor he took an interest in its medicine, as a devout Christian he knew that the Biblical books of Genesis and Exodus are set in ancient Egypt; and as a scholar of comparative religion he was familiar with the names and attributes of the Egyptian gods; but above else its from his adherence to Hermetic philosophy that Browne's life-long interest in the Land of the Pharaoh's was sustained. For, in common with almost all alchemists and hermetic philosophers of the 16th and 17th century, Browne believed ancient Egypt to be the birthplace of alchemy and where long lost transmutations of Nature were once performed. And indeed the early civilization skills necessary in baking, brewing and metal-work, as well as cosmetics and perfumery, were all once close guarded secrets. Ancient Egypt was also believed by hermetic philosopher and alchemist alike to be the home of the mythic sage Hermes Trismegistus, inventor of number and hieroglyph and the founding father of all wisdom subsequently passed down in a golden chain of prophets and mystics culminating in Christ.

Just as fans of the pop singer Elvis Presley (1935-77) often collect all kinds of American memorabilia, so too in the 16th and 17th centuries followers of Hermes Trismegistus avidly collected artefacts believed to be of Egyptian origin, and read literature which claimed to be by the Egyptian sage.

Browne's adherence to Hermetic philosophy is writ large in his spiritual testament and psychological self-portrait Religio Medici (1643), the newly-qualified physician declaring - 'The severe schooles shall never laugh me out of the philosophy of Hermes, that this visible world is but a portrait of the invisible.' [1]

Its however more with an eye towards dentistry and with characteristic humour that Browne in the consolatory epistle A Letter to a Friend informs his reader -

'The Egyptian Mummies that I have seen, have had their Mouths open, and somewhat gaping, which affordeth a good opportunity to view and observe their Teeth, wherein 'tis not easie to find any wanting or decayed: and therefore in Egypt, where one Man practised but one Operation, or the Diseases but of single Parts, it must needs be a barren Profession to confine unto that of drawing of Teeth, and little better than to have been Tooth-drawer unto King Pyrrhus, who had but two in his head'.

Browne's knowledge of Egyptian medicine was acquired through reading the Greek historian and traveller Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE) whose Histories was the solitary source of information about ancient Egypt for centuries. [2] In Browne's day there was a well-established trade in mummia. Because the skills in Egyptian mummification appeared to preserve the human body for the afterlife in an extraordinary way, the crushed and pulverised parts of Egyptian mummies became popular remedies for all manner of disease and illness. Often mixed or contaminated with bitumen, in reality mummia was of little medicinal value. Thomas Browne for one, deplored its usage in medicine, declaiming in Urn-Burial -

In the foreword to Mysterium Coniunctionis; 'An inquiry into the separation and synthesis of psychic opposites in Alchemy', the seminal psychologist C. G. Jung informs his reader that -

'the "alchemystical" philosophers made the opposites and their union one of the chiefest objects of their work'. [7]

I've written before about how Thomas Browne's diptych Discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus exemplify the Nigredo and Albedo stages of the alchemical opus - of how the two Discourses are opposite each other in respective theme, imagery and truth. The dark and gloomy doubts, fears and speculative uncertainties upon Death featured in Urn-Burial are mirrored by cheerful certainties in the discernment of archetypal patterns in The Garden of Cyrus - of how the two works fulfil the template of basic mandala symbolism with their metaphysical constructs of Time (Urn-Burial) and Space (The Garden of Cyrus) and of the many polarities which they display such as - World/Cosmos, Earth/Sky, Accident/ Design, Decay/Growth, Darkness/Light, Conjecture/Discern, Mortal/Eternal and of course, Grave/Garden.

The concept of polarity (a word Browne is credited with introducing into the English language in its scientific context) is a vital construct of much esoteric schemata. The opposites and their union, as C.G. Jung noted, were a fundamental quest of Hermetic philosopher and alchemist alike. Browne’s literary diptych is, not unlike the human psyche, a complex of opposites or complexio oppositorum (complex of opposites). Unique as a literary diptych, it corresponds to the polarity of the Microcosm-Macrocosm schemata of Hermeticism in which the microcosm little world of man and his mortality, (Urn-Burial) is mirrored by the vast Macrocosm and the Eternal forms or archetypes (The Garden of Cyrus). The polarity of the alchemical maxim solve et coagula (decay and growth) also closely approximates to the diptych's respective themes, as does the diptych's imagery which progresses from darkness and unconsciousness (Urn-Burial) to Light and consciousness (Garden of Cyrus). The previously mentioned alchemical feat of palingenesis, that is, the revivification of a plant from its ashes which the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus (1493-1541) claimed to have performed, shares close semblance too. The funerary ashes of Urn-Burial burst into flower in the botanical delights of The Garden of Cyrus.

C.G. Jung stated that whenever a complex of opposites occur, a unifying symbol, capable of transcending paradox, sometimes emerges. Its far from improbable that Browne found in his study of ancient Egypt two such symbols which he subsequently embedded in his Discourses namely, the Egyptian god Osiris and the Pyramid. As the literary critic Peter Green noted, 'Mystical symbolism is woven throughout the texture of Browne's work and adds, often subconsciously, to its associative power of impact'. [8]

Osiris was one of the most important gods of Ancient Egypt. He plays a double role in Egyptian theology, as both the god of fertility and vegetation and as the embodiment of the dead and resurrected king. Osiris is utilized in Browne's proper-name symbolism in Urn-Burial as an example of how Time devours even the names of the gods themselves - 'Nimrod is lost in Orion, and Osyris in the Dogge-starre'. However, in The Garden of Cyrus the Egyptian god Osiris assumes a more important role, as the god of vegetation and growth who is assisted by his secretary, the great Hermes Trismegistus. In a short paragraph in which the game of Chess, Pyramids, Egyptian gods and astronomy coalesce in an extraordinary stream-of-consciousness association, Browne exclaims -

'In Chesse-boards and Tables we yet finde Pyramids and Squares, I wish we had their true and ancient description, farre different from ours, or the Chet mat of the Persians, and might continue some elegant remarkables, as being an invention as High as Hermes the Secretary of Osyris, figuring the whole world, the motion of the Planets, with Eclipses of Sunne and Moon'.

C.G. Jung noted how Egyptian theology influenced Christianity thus-

See also

On esoterism in 'The Garden of Cyrus'

Carl Jung and Sir Thomas Browne

Paracelsus and Sir Thomas Browne

Books consulted

* Browne: Selected Writings. ed. with an introduction and Index by Kevin Killeen Oxford 2014

* Herodotus : The Histories. Penguin 1954

* Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man the Quest for Lost Knowledge

- ed. J. Godwin Thames and Hudson 1979

* C.G. Jung Collected Works Vol. 14 Mysterium Coniunctionis

* 'Egypt' BBC DVD 2005

* 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue of T. Browne and E. Browne's libraries

* Author's 1658 edition of Pseudodoxia Epidemica with Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus

Notes

[1] Religio Medici Part 1:12

[2] Book 2 of Herodotus The Histories includes his observations on Egypt.

[3] 'In his learned Pyramidographia' Browne marg. of 1658 3rd or 4th edition of P. E. Bk 2 chapter 3

[4] R.M. Part 1:34

[5] P.E. Bk 2 ch. 3

[6] Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man the Quest for Lost Knowledge J. Godwin. 1979

[7] C. W vol.14 Mysterium Coniunctionis Foreword

[8] Sir Thomas Browne Peter Green -Longmans and Green 1959

[9] C.W. Vol.9 part 1: 229

This one for M. with thanks for encouragement.

Saturday, November 07, 2020

William Taylor of Norwich - 'Kräftig, aber klappernd'.

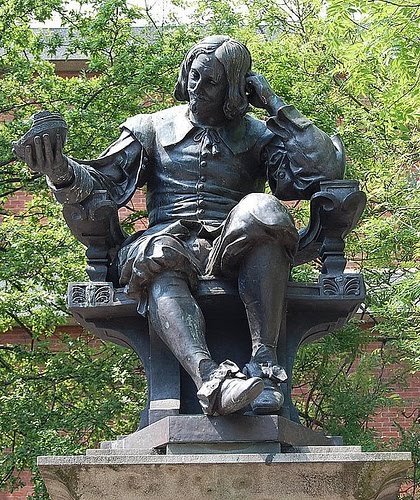

William Taylor's friendship with Robert Southey (above, circa 1795) began in 1798 when Southey visited Norwich as Taylor's guest; the poet revisited him at Norwich in February 1802. In correspondence to Taylor, Southey asks him-

.jpg)

_blu.svg.png)